100-76 | 75-51 | 50-31 | 30-11 | 10-1

Can desire best be described as a train running into a tunnel? In popular culture, desire is rarely written with the nuance (or maybe, the trepidation) it deserves, reduced as it is to the slickest surface of its skin and hardly deeper. Sex is a commodity that enforces possession and hierarchy, something to receive or give depending on a narrative. In music production, we can find erotic platitudes that extend the length of an appendage environed by the digital squalor of diamond-studded algorithms. Pop music, great trains, running into tunnels: sex as a deliberate force acted upon us by the external forces we internalize and, by god, in turn, externalize. Art as submissive constructs to societal norms. If not trains, what then?

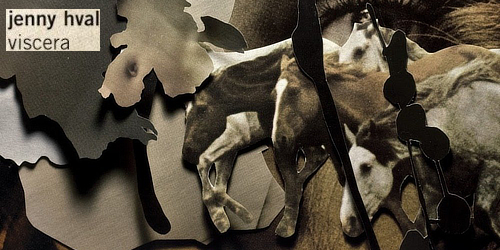

The answer Jenny Hval offers is immediate, though you’d be forgiven for thinking it the iconic opening gambit: “I arrived in town / with an electric toothbrush / pressed against my clitoris.” Rather, we are drawn inward by the quiet intensity of her arrangements, in the discordant ambiance that slowly envelops the stark percussive elements. There is a timeless quality to the mixture of industrial and folk music, in the glacial way the tracks erode and subside only to build into discomfiting calamity. The songs unspool with seeming spontaneity to an unapparent trajectory, lending the baroque stylings a delicate verve; the effect is a magnetism not typically reserved for art-pop made with such unconventional, arch methods.

But always a symbiosis, an equilibrium between the album’s explicit and obsessive themes of female sexuality and expression— of the flesh and travel— and that of its music. The female body is not monstrous, nor is it glamor; it is, as all bodies are, a composite of its own wastes and longings (“The body remembers / in a distant memory” on “Golden Showers”). But never has it been written about such like this, as candidly “frightening, but also ecstatic.” Again, that opening line, the intonation of “cli – tor – is.” Viscera touches upon its themes so intimately as to be instructive, to know the limitations in language but also its commanding presence, especially that which is adopted from a society where innocence is considered kinky. Can desire best be describe as a train running into a tunnel? Only for those who lack the imagination, or the inspiration, of an album like Viscera. –plane

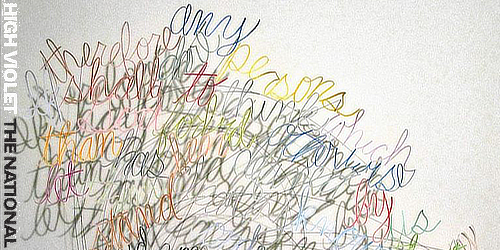

Well, we can all stop arguing amongst ourselves – the Sputnik staff has collectively declared High Violet to be the best National album of the 2010s (not of all time, sorry – that’s Alligator of course. (Yes, we were wrong the last time we did one of these). For many, High Violet is the unimpeachable conclusion to an era-defining trilogy, a decade-crowning culmination of all the little fuck-ups that broaden and calcify to create the map of a life. What the National generally, and Matt Berninger specifically, have in spades is that crucial skill every other middlebrow indie rock band wishes they had: the ability to express and twist mundanities into relatable, highly hummable tunes. That nagging self-doubt and habitual worrying that newfound fatherhood brings in “Afraid of Everyone”; the meaningless inertia of modern life in “Conversation 16”; “all the very best of us string ourselves up for love.” These aren’t exactly new or fresh sentiments, particularly in the context of the National’s discography, but during this run of classic albums Berninger was never one to sound like he’s just going through the motions. On High Violet, he occasionally veers close to self-parody – the band’s infamous six-hour live replay of “Sorrow” implicitly acknowledges this – but that effortless baritone somehow manages to toe the line perfectly through each of these eleven tracks.

High Violet excels in deftly handling the Big Topics – love, death, depression, that mountain of debt you’re never going to get out from under – without sinking into cliché and, perhaps more impressively, without retreading ground already covered. “Sorrow” is more than its title; it contemplates the sort of fear that never leaves you, that instead travels with you quietly, unacknowledged and unassuming. Will I still have a job tomorrow? Is that voicemail lurking on my phone my mother’s test results? What happened to all my old friends, and that familiar stranger in a yellowed photograph? The lesson of “Sorrow” is that this sort of constant fear is just another fact of life, unavoidable but somehow comforting in its consistency. To act otherwise is to not be able to get on with life. “Runaway” describes a tempestuous relationship in biblical terms – “what makes you think I’m enjoying being led to the flood?” – but Berninger avoids the melodrama this characterization implies by couching this spiraling romance in one of the band’s warmest tracks and the muted re-assurances of the unsure: “I won’t be no runaway cause I won’t run.” Yet at the end of it all, the realization is inevitable: “We got another thing coming undone / and It’s taking us over / and it’s taking forever.” Sometimes, things just need to end. That’s okay, too. Berninger is more mature here than he was on the unstable Alligator and the uncertain Boxer, more willing to take paths forward rather than back.

For some other fans, though, High Violet served as the initial instance of diminishing returns, the first crack in the foundation of a sound that is often imitated and occasionally caricatured. The sound is essentially a more expensive Boxer, they say. They point to the facially inane lyrics of “Lemonworld” and Berninger’s sighing “do-do-do’s,” or the rote heartbreak of “Anyone’s Ghost,” as direct precursors to some of the generic, extremely on-brand National tracks that would follow. Just add your choice of a dash of self-doubting existentialism here or decaying suburbia there, they contend, and presto! I am pleased to report these naysayers are idiots; “Lemonworld” is one of High Violet‘s best tracks and “Anyone’s Ghost” is good, actually. Sure, “Runaway” sort of just glides by and “England” takes far too long to get where it’s going, but these are cheap shots. The same critic can deride High Violet as an unearned rehash, but where High Violet exceeds the (admittedly high) standards set by the band’s other work is in its meticulous arrangements and textured palette. What if Boxer, but sonically interesting? *Dodges tomatoes* The National were in full command of their faculties on their fifth record, everything in its place and as it should be. Simply put, there is no dead weight here, from the titanic swell of “Bloodbuzz Ohio” and the foreboding strings and unobtrusively complicated rhythm work on “Little Faith” to the seemingly idyllic life in “Conversation 16” transformed into a suffocating horror movie soundtrack and the cathartic release of “Vanderlyle Crybaby Geeks.” Anyone can make the argument the National are essentially plagiarizing themselves on every new record. I’d argue such a criticism speaks to the group’s astounding success at crafting a sound that is inextricably associated with the National – like pornography, you know it when you see [hear] it. High Violet, though, remains the apotheosis of that sound, a fitting summation of the emotional journey the band chronicled throughout the 2000s and the last time Berninger and company crafted an album that felt truly lived in, inseparable from the angry young man of Alligator and Boxer‘s professional ennui. Throughout the rest of this decade, the National became experts at telling stories. On High Violet, they finally mastered telling their own. –klap

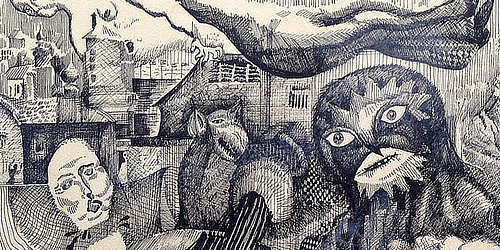

The Seer was my introduction to Swans – the loudest, most hypnotic band in the world. As the decade list was being compiled into what you see today, it was obvious – judging by at least one of the three albums making a lot of the staffers’ lists – that Swans had made one of the most timeless, artistic statements in rock music’s history. The Seer, To Be Kind and The Glowing Man form one of the most flawless trilogies of our time, pitted in a decade where platitudes of rock being “dead” maintained their firm consensus. This trilogy proved otherwise though, with its sprawling and expansive visions, mind-bending run times, and ambitiously hypnotic and distinct soundscapes. In fact, it’s hard to talk about just one of these LPs without referring to the other two which accompany it, because they’re so intertwined with one another, but if I had to pick one of these three masterpieces, it would be The Seer. From the artwork’s unsettling wolf, which has Gira’s teeth modelled into the shaggy beast’s head, to the densely oppressive, ritualistic moods The Seer so passionately exudes.

This LP in particular has something minacious and unhinged about it when compared to the other two records. The title-track’s repetitive thirty-two-and-a-quarter-minute trance should have devastating consequences on the album – its monotonous exercises would certainly derail any other band’s daring attempts – but for some reason, The Seer and its proceeding installments have a rhetoric and allure that possesses the listener; an introduction into its whirling, rhythmic labyrinth. It also helps that Gira is self-aware enough to know that after such a long-winded bout with unsettling ambiences, we get a good dose of seductive, Lynchian-styled grooves, haunting electronics, and the beautifully composed “The Daughter Brings the Water” to wrap up the first half of this mammoth peregrination, as a reward for sticking with it. And that’s an important factor to take into account with The Seer‘s success, because for all the unsettling, nightmarish loops that stretch on for what can feel like a generation, it knows when to bring the meat and potatoes to the table. And, oh boy, does the second disc of this album throw the kitchen sink at its audience.

You see, the first part of this album is definitely a setup to a much bigger scheme. It lets you get comfortable with its bleak-yet-gorgeous world before unleashing its true potential. Where the first half of the LP brings abrasive electronics to the forefront, the latter portion of the album becomes far more melodic. From the phenomenal and relaxing folk-rock epic “Song for a Warrior”, which is delicately sung by Karen O over acoustics and bright electric guitars, to the post-rock voyage of “A Piece of the Sky”, there’s a much broader variety added to the canvas. The gargantuan, colossus-bounding “Avatar” with its awe-inspiring build ups, right through to the Tom Waits-styled barks Gira unleashes on “Apostate”. For anyone wondering why this album has the reputation it has, it’s largely in part to the second half of the album, which delivers, and exceeds, in so many ways.

The album’s title is defined as a prophet – someone or thing that can see beyond the realm we envisage – and when you put that into context with the album, it’s easy to see a spiritual undertaking at play here. This is one of the most unique albums I’ve ever heard, there’s just something about it that pulls me into its world the moment it starts. From the sacrificial chanting in “Lunacy”, and the hypnotic panting in “Mother of the World”, right through to the closing seconds of “Apostate” – a song that defines the meme “hold my beer” before blowing the doors off of its idiosyncratic wonderland – this whole record feels and sounds like nothing else. There’s a presence within The Seer that lingers for the entire two hours; it’s a feeling almost out of reach with words, and one you have to experience for yourself to fully understand it. But to me, it’s the feeling that The Seer was composed by an ensemble of deities, and for all intents and purposes, I don’t think I can give a bigger praise than that. –Simon

mewithoutYou create magic–not in the mawkish sort of way, but the mystical, one-of-a-kind way that’s breathed into life by the ambiguous spirituality and winding stories of Brother, Sister andIt’s All Crazy! It’s All False! It’s All a Dream! It’s Alright. They are a singular entity, one which challenges and bewilders with whimsical fables and apocalyptic visions in equal measure. Pale Horses, frankly, offers none of that. Comparatively, their penultimate (???) recording feels grounded–turning the stream of consciousness into a vernal pool. It’s a summation of a diverging career that forked into post-hardcore, non-secular alternative, and art-house rock.

Okay this is where I give in–mewithoutYou are difficult to talk about, especially retrospectively, and especially in the post-mortem. That magic I tried putting into words is *real*–it’s what makes me remember the exact moment I fell in love with that last minute of “O Porcupine,” or how “In a Sweater, Poorly Nit” became the soundtrack to an entire summer. Pale Horses takes all I’ve ever loved and hated about the band and puts it into this ineffably perfect collection which ranges from the jagged “Red Cow” to the hazy, blissed-out “Rainbow Signs.” I want to be one of those people who can write intelligently about Pale Horses, and by extension, mewithoutYou–but I can’t. I want to tell you why “Mexican War Streets” is a best-of-the-decade contender–but I can’t. It’s impossible for me to capture it, but you know what? It’s great believing in magic again. –Eli K.

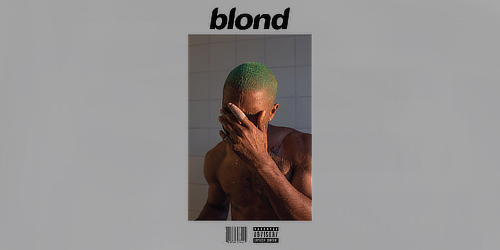

“How far is a lightyear?” is the question Blonde leaves us with, after precisely an hour of dream-hazed, skeletal R&B where the unsaid things between Frank Ocean’s lines are more important than the lines themselves (see: the implicit heartbreak in “Ivy”‘s face-saving “we both know that deep down, the feeling still deep down is good”, or the devastating evocation of the distance between two people next to each other in a car of “White Ferrari”). Blonde is about distance, is my point – the distances we put between ourselves and the ideals we don’t plan to reach (“Seigfried”), between love and lust (“Solo”/”Self Control”), between the love we think we deserve and the one we had to let go (“Godspeed”). In this way, I’d argue Blonde is one of the most well-rounded concept albums of the decade. Even the interludes, clunky as they are, function as a list of the things that have widened the space between people – drugs, social media, the weight of expectations in the digital age.

With the benefit of hindsight, I might offer Endless as Ocean’s best release. It goes further than Blonde by extending the anxieties of the ADD generation down to its format: fractured, ephemeral, lovably scatterbrained as the best of mixtapes. But there’s no denying the immediate and sustained impact Blonde has had on the game. Only a year later, Lorde took it into the mainstream, dropping an intensely personal, fractured concept album about failing relationships with a two-part song and electronically treated reprise in amongst some of the catchiest songs of the decade. James Blake pushed further towards pop as if chasing the gorgeous sweet spot between melody and dissonance that “Ivy” and “Self Control” perfected. Pop music became bolder, stranger and somehow more intimate this decade. These movements were fantastic, but none have yet captured that feeling of distance, real or imagined, inside their notes and words as powerfully as Blonde. Nothing, in this writer’s estimation, has yet topped that final minute of “White Ferrari”, where all pretense of artistic remove falls away and Ocean sings his best lyric over that butterfly-fragile backdrop. “I’m sure we’re taller in another dimension, you say we’re small and not worth the mention”.

And so again we find ourselves at “how far is a lightyear?”. Trillions of miles is the actual answer, but with the autumnal glow of “Futura Free”‘s tape fading, a heartwarming montage of childhood life that somehow makes the rest of the album before it feel desperately lonely and cold, the question takes on a different meaning. When you look at someone you love next to you in a car and feel lightyears of distance between you, how far is that? However far we make it, seems to be Ocean’s only answer; letting this question hang in the air, after an album of breathtaking sketches of the isolation of our new global community, ensures Blonde will remain one of the most challenging and confronting albums the pop sphere has ever produced. –Rowan

5. Sufjan Stevens – Carrie and Lowell

When considering the greatest folk records of all time, I often find myself imagining what it was like to experience Pink Moon, Bridge Over Troubled Water, or Blonde on Blonde (all of which came before my time) firsthand. Sure, a cursory search can determine the critical reception of these albums around their respective release dates, but for the longest time I craved the feeling of stumbling upon an all-time gem and immediately knowing it; something not merely enjoyable but also of historical significance within its genre. 2015 ended that long wait when Sufjan Stevens, stripped of all pomp and frills, released his undeniable masterpiece in Carrie & Lowell. This is the folk album of our generation – a bruised, drug-riddled, depressing account of death that doubles as a timeless classic.

Carrie & Lowell isn’t the greatest folk album of the decade because of its pastoral instrumentation or pristine production – although those both contribute to the record’s uniquely haunting atmosphere. Its real value comes at the expense of Sufjan’s suffering, a gaping emotional wound left by the death of his estranged mother. The experience becomes more gut-wrenching the more you research the album’s backstory. Sufjan’s mother, Carrie, abandoned Stevens and his siblings when he was only a year old as a labor of love to prevent them from being exposed to her schizophrenia and drug addiction. Their father was distant, raising them like tenants while keeping an emotional arm’s length. Sufjan clung to a swimming instructor as a role model while falling into depression, drug addiction, and suicidal thoughts himself. All of this speaks to exactly why it feels so unwholesome to say I “enjoy” Carrie & Lowell; anybody who’s listened to this knows that it isn’t a product to be consumed for pleasure. It’s Sufjan’s unread letter to his deceased mother; an account of his journey beginning with her abandonment and ending with his attempts to process her death (the irony of grieving the loss of a person who was never truly present isn’t lost on Sufjan here, either). Ultimately, it’s a record brimming with sadness and confusion, as Stevens desperately attempts to fill in his life’s puzzle with dozens of pieces missing from the set.

This experience is at its most crushing when Sufjan peels back all his defense mechanisms and exposes his shattered core. Stevens has made a career of telling tales via elaborate themes and over-the-top exhibitions of grandeur, but Carrie & Lowell takes a sledgehammer to all of that and allows a rare glimpse into his world. It’s most evident when he opens up lyrically about his relationship with his mother, such as the deathbed reconciliation that occurs on ‘Fourth of July’ where he quotes Carrie directly: “Did you get enough love, my little dove?…I’m sorry I left, but it was for the best, though it never felt right.” When he finally becomes overwhelmed on ‘No Shade in the Shadow of the Cross’ and sings “fuck me I’m falling apart”, it hits ten times harder because of all the mini-stories that laid the foundation for such an emotional breakdown. It’s also the reason why we can surmise that the preceding line, “there’s blood on that blade”, alludes to Sufjan cutting himself – a reference that originated on the subtly suicidal ‘The Only Thing.’ Sufjan Stevens does an incredible job of layering his confessional lyrics and structuring the album in such a way that almost every verse recalls an earlier one, resulting in a series of gut-punch realizations. It’s hands-down the most devastating account of death and inner turmoil that I’ve ever heard. Carrie & Lowell certainly isn’t the most readily digestible album to come out in the last ten years, but it is just as assuredly one of the best. –Sowing

4. Kanye West – My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy

It’s easy to forget after countless delays, mental breakdowns, and disappointing finished products that followed it, but My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy was the peak of big-budget hip hop. Back in 2010 – a time when Ye was at least sort of coherent – Kanye West was on an apology tour after interrupting Taylor Swift at the VMAs the previous year. The experience (sort of) humbled West, and a tour cancelation as a result of the controversy allowed West the time to seize upon the opportunity to write his most poignant lyrics and darkest beats to date. Ten years later after several self-indulgent and sometimes mean spirited records like Life of Pablo and Ye, MBDTF feels quaint by comparison. His struggle with being the bad guy, a role he embraced on his very next record, is what makes this album so special. MBDTF is peak Kanye, and it kicked off the decade with a bang.

My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy is not as influential nor emulated as heavily as 808s & Heartbreak, but that’s a testament to the fact that no one could possibly make an album like this. It’s so epic in scope and sound and it’s the kind of album where every song is someone’s favorite. “All of the Lights” is catchy beyond belief, “Monster” has huge verses, “Devil in a New Dress” is the epitome of cool, and the backbone to all these tracks is the multi-layered beats constantly shifting and changing, like the orchestral tones in “So Appalled” that drape the verses. This was the beginning of a much darker Kanye. It’s also the most lyrical he’s ever been, with more fleshed out and realized concepts than his earlier work, and lacking the “fuck it here’s my first draft” energy of his more recent work. MBDTF is the perfect time capsule of a simpler time when Donald Trump was merely a rap song punchline and Kanye might choke a South Park writer with a fishstick. It has its bloat for sure, Runaway is about a minute and a half too long, that Chris Rock comedy sketch gets old after the fifth listen, and both of Jay-Z’s verses are garbage, but My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy is peak genius Kanye, it’s right there in the title, and it’s the best hip hop album of the 2010s. –Trebor.

If one was to take a shot and lose a digit for every live band clearly emulating Sonic Youth, Talking Heads, This Heat during the period of 2006 and 2010, one would find oneself inebriated to the point of poisoning, lacking one’s opposable thumbs. Yet it was comparisons to these bands that led me to discover Public Strain: I was painting houses in small town New Zealand (so, uhh, super small town America) and listening to all the afore-mentioned as if on a diet when Public Strain was recommended to me.

I’d be lying if I said it was love at first sight, or that that the comparisons held true. It was too arch, too haughty, too cold, and though I recognized the beauty it seemed too arcane and impenetrable, a recondite gorgeousness I couldn’t parse. But call it seduction: I kept returning, kept listening. A decade later and it’s one of my favorite albums of this decade or any. How?

The album sounds impossibly, perfectly calibrated, with even the fug of noise that opens Can’t You See, noisy expectorations of Drag Open, squeaky drum of China Steps, sounding as precise as a clinical insertion, every drawled lyric and guitar line calculated. Yet it’s this precision that ironically – paradoxically – opens the album up to interpretation and emotional effect. The fog of Can’t You See climaxes and commingles in a gorgeous, harmonious drone; Drag Open unfurls, China Steps just fucking bangs, Bells proves itself integral, not interstitial as previously thought, and not a piece is missing in the jigsaw of sound design (credit, here, to Chad Vangaleens pristine production). Penal Colony and Venice Lockjaw offer languorous respite, a canoe drifting serenely downriver – full of holes. Women had supplanted their influences and offered a challenge so far unmet, unwittingly creating a death knell – after this, where was Indie Rock went to go?

If one was to take a shot and lose a digit for every band that emulated Public Strain, then, you’d be in better stead. Though a couple sought to replicate that album’s aloof genius, and on one amusing occasion I witnessed a band try to pass Heat Distraction off as their own, the precision and the recondite beauty were so clearly impossible to capture few bands tried. Another thing happened: a cultural shift in which Indie Rock is bound by socio-political statement, anchoring it to time. Yet here, too, Public Strain endures. It is a remarkably ageless album, existing out of time or of capital m Movement, existing in its own category. I no longer go to Indie Rock concerts, much: instead I’m happier lowering the needle on the A-side of Public Strain, watching the fog coalesce into a shape which morphs into four of them and it’s beautiful, beautiful, beautiful. –Winesburgohio

At first we wanted to answer questions like, “What is Flying Lotus interested in? What does he make albums about?” But then we read Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s piece on the director Douglas Sirk, where he writes that “You can’t make films about something, you can only make films with something, with people, with light, with flowers, with mirrors, with blood, with all these crazy things that make it worthwhile.” Cast aside the obvious differences between films and music for a second: What does Flying Lotus make music with? As Fassbinder implies, shifting our focus from the “about” to the “with,” from the “what” to the “how,” is a lesson all of us self-considered art critics should periodically re-experience. What kind of experience does Flying Lotus, with the materials at his disposal, create?

The experience is big–one notices, while listening and reading, the tactile way in which this music invokes reverential responses to its stimuli, so that we understand the “cosmic” embedded into its title to mean Heaven or something like it through its grand force and scale, its sheer power. Let’s make no bones about why we’re here, at this point on a big list filled with big records: this is the most impressive electronic album to be released this millennium, a judgment made with all due respect toward genre stalwarts that become profound inflections within this new composite language of (deep breath) techno, hip-hop, neo-classical, “intelligent dance music,” avant-garde jazz, video game music, house music, etc. etc.

Again: what kind of experience does Flying Lotus, on Cosmogramma, create, or at least desire to create? Flying Lotus–let’s call him Steven Ellison, for now–lost his mother on October 31, 2008, 21 months after the death of his great-aunt Alice Coltrane. Ellison had just released his breakthrough LP, Los Angeles, and started work on the album that would become Cosmogramma, a process that involved recording his mother in her hospital bed. “I know it was a weird thing to do,” Ellison would tell the Los Angeles Times in the spring of 2010. “But I didn’t want to forget that space.”

Cosmogramma, a record of one man’s desire not to forget the memory of his mother and the loss he was soon to experience, is itself unforgettable. This extraordinary quality plays out on a micro- as well as a macro-scale. As “Clock Catcher” turns to “Pickled!” and then into “Nose Art,” and “Nose Art” into the wryly titled “Intro” and beyond, one remembers the characteristics of each track that has passed by, quite clearly in fact: “Clock Catcher” with its successive burps and barbs of synth; “Pickled!” with its ear-shattering pitch/tone/noise/thing ripping a hole in the sonic fabric; “Nose Art” with its charmingly clunky percussion and stepwise bass. And then one remembers clumps of the whole experience, as well: the softness of “Table Tennis” poised against the magisterial thump of closer “Galaxy in Janaki”; the way “German Haircut” brings things to a syrupy deceleration. How Thundercat’s career-best vocals-and-bass performance on the immensely moving “MmmHmm” (“Just be who you are…”) slips quickly into the glass slippers donned by Ellison for the weirdo intergalactic midnight dance party that is “Do the Astral Plane”. And then one–slowly, perhaps imperceptibly–remembers the entirety. Not quite a detectibly elegiac homage to his deceased mother in terms of its content, Cosmogramma goes one layer deeper, paying respects to its artist’s loved ones through its structure and form. What better way to use the power of art in order not to forget than to generate an indelible experience–one which formalizes, even if it does not directly refer to, the irreplaceable effect of the beloved on the artist?

Again: What does he make his albums with?

The first sound we hear on Cosmogramma is an E, followed quickly by a E-flat, both played on a sort of gulpy rounded-edges keyboard patch. A note, followed by the note that is a half step down. That’s our first taste. You don’t need to know music theory in order to hear the weird, lightly prodding association between the first half-second of this record and the perilous vibe of something like, why not, the James Bond theme song? Same melodic idea, anyhow: the Bond song hinges on a half-step downward from E-flat to D–that is, the same miniature melodic idea that opens “Clock Catcher,” modulated one half-step down. Or how about the Super Mario Bros. 2 “Game Over” song, which concludes melodically with a half-step from F to E, the same pattern modulated one half-step up from the “Clock Catcher” intro. Flying Lotus is nothing if not a knowingly allusive musician and manipulator of minds; without claiming a specific reference point on his behalf, he knows that this two-note pattern settles pleasingly somewhere in our unconscious between Mario and James Bond, or between more general affective concepts, between something like “Something has just ended for me and I don’t know what it means” and something like “Let’s fucking GO.”

Vying for supremacy with this two-note motif, which is never to be heard from again, Flying Lotus dropping it as soon as it materializes, is a laugh. “Heh-heh-heh-heh.” Flying Lotus adduces laughter on a later song on the album, one featuring Thom Yorke, titled “…And The World Laughs With You”. That title is drawn from a poem called “Solitude” written in the 1880s by an oft-maligned poet named Ella Wheeler Wilcox; the poem begins, “Laugh, and the world laughs with you; / Weep, and you weep alone.” What intrigues Flying Lotus about the mechanics of laughter? Henri Bergson, sounding a bit like Wilcox, wrote in 1900 that “You would hardly appreciate the comic if you felt yourself isolated from others. Laughter appears to stand in need of an echo…” He also wrote that laughter is about something being involuntary: a man suddenly deciding to sit on the ground is not funny, does not produce laughter, but him falling flat on his ass is, does. Cosmogramma is worth a laugh. The album is a) social, equally because of its network of referential sonic material and because it brings people together, and it is b) something you experience, dare it be said almost involuntarily. “Involuntarily” not because you didn’t choose to listen to it–if you’re like us, you’re almost always choosing to listen to this record–but because of the unearthly pace and structure of this thing, which never wears out: Cosmogramma happens to you.

So, back to that introductory laughter that accompanies the two-note motif, pulsing four times: heh, heh, heh, heh. The laugh, a reflexive acknowledgement and embodiment of FlyLo’s innate sense of chaos, and those two notes…it’s like they’re locked in an embrace, both of them saying the same thing differently: you’d better hold onto your asses, folks. Here we go. Controlled by a man of such inimitable instincts throwing sonic elements together helter-skelter so that it comes off as truly “involuntary,” Cosmogramma is the sound of–as Thom Yorke once put it–everything in its right place. Which is also, sort of, everything in its wrong place. Which is, like, sort of how the world works, right? Because Cosmogramma is a world. And the “how” of this world’s machinations are so fucking genius, so playful and canny, straddling the boundaries of anarchy and discipline like there weren’t any boundaries to begin with, that you want to just laugh…and the world–this world, the world of Cosmogramma–laughs with you. All of this and more sprouts from within what Spotify assures me is the first second of this album, before “0:00” transforms into “0:01”.

Zoom out again. Cosmogramma is the thrilling sound/sounds/every-sound of an impresario at the height of his powers using music in an instructive, vulnerable way, to reconcile his obsession with dreams and out-of-body experiences with that of the incredible unknowing that drives human progress: of life, of love, of death, of the eons contained in atoms.

Heady stuff. But such are the responses cued by the warped sense of scale Flying Lotus commands, the delirious jubilance to and with which he conducts his arrangements. And what makes Cosmogramma a decade-defining masterpiece is the confidence of its display, the resounding wholeness of its speech, a testament to the wonder and peculiarity of what, damnit, Flying Lotus makes music with, whether it be from his computer, a violin, or samples of his mother’s death bed. Under his command, they all speak in the great mother tongue of the cosmos. –robertsona & plane

1. The Hotelier – Home, Like NoPlace Is There

In moments of self-reflection, I find that my most favorite of my many, many flaws is my inclination to ascribe sentiment to just about anything that I can. I’ll find any excuse to not throw something out if there’s even the slightest semblance of a memory associated with it, because I happen to believe that a life can really only be measured in terms of memories. Memories traverse time like nothing else can, and for most of humanity’s reign on earth they served as its most basic currency of experience. These days, we find ourselves a few decades into an age where it’s worth asking how data and memory interact, and what role a memory can truly occupy in an age where there’s so much you can just look up.

I first listened to The Hotelier’s Home, Like NoPlace Is There on February 27, 2014, at 9:56 am. That was a Thursday morning, two days after the album came out (back when new records came out on Tuesdays). At 9:56 am, I was at 155 Water Street in Brooklyn, New York. It was 27° F outside when I hit play. Exactly six minutes before I first heard “An Introduction to the Album”, I googled “mlb standings 2013,” and then proceeded to visit the ESPN page for baseball standings. At that exact moment, me and my two closest friends were debating what the Mets’ record would be in the 2014 season. At 9:54 am, I sent a message that read “yea 79 wins.” The 2014 Mets would go 79-83. Later that evening, I would comment “yea its pretty bad but ive seen worse” on Atari’s review of the record, which was in response to Robin’s note “what is that fucking summary.” Later that evening, Trebor commented with a YouTube link to an acoustic session, and I watched it. Almost exactly six years later—off by just two days, actually—myself, Atari, Robin, Trebor, and several other staffers, both active and emeriti, decided together that Home, Like NoPlace Is There was the album of the decade.

O-PEN THE CURTAINS, the album famously begins, and it does so with a chilling take on what would otherwise be gesture of welcome. It’s chilling because of the sheer power of the line, and because of Christian Holden’s voice – crisp and clear, and every bit as essential on those first three words as it is on the ones that follow it. While Home is certainly an album that has aged well musically—the songs are still catchy and massive in the same ways they were in 2014—the record’s more impressive feat is how even the sad things it may have made you feel years ago are immediately welcomed back. This is, of course, a record packed with individual songs that are lyrically about grief and toxicity, but something more serene comes when the sum of all this viscera is taken as a larger work. It is a composition about exorcising memory through wallowing in each fucking moment, and that is the kind of catharsis that really resonates over time. Most critically, it’s one that no statistic or measurement can adequately communicate.

So please forgive my gross, romantic obsession with data, and please also humor my attempts to parse out the heartfelt bits of a decade spent growing up, learning things, and listening to jams from the teRRIFYING HELLSCAPE THAT IS A REALITY WHERE THE MOST POWERFUL CORPORATIONS IN THE WORLD HAVE ACCESS TO ALL OF THAT AND WHO KNOWS HOW MUCH MORE… Sometime in between when I watched Trebor’s video and when we all submitted our individual lists, Atari had amended the summary of his review. I wonder what the original one was. I think it might just hit me a little differently today. –theacademy

Contributing Staff Members:

Atari | AtomicWaste | Ben K. | BlushfulHippocrene | Channing Freeman | clavier | Eli K. | Frippertronics | IsItLuck? | Jom | klap | manosg | Matt Wolfe | plane | robertsona | Rowan | Simon | Sowing | theacademy | Trebor. | Tyler | verdant | Willie | Winesburgohio

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

And The Hotelier at #1 is well... pft.

04.10.20

lil bit sad that Sit Resist didnt make it but w/e

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

(There Will Be Fireworks would have slotted in nicely somewhere though!)

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

are you somehow even remotely surprised by this fact?

04.10.20

I enjoyed reading this regardless so cheers everyone.

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

Cracking job everyone

04.10.20

04.10.20

But Hotelier #1 is well... pft [3]

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

I'm glad someone else picked up on that parallel. I love when we have a consensus #1 that you wouldn't find anywhere else. Furthermore, that it was preceded by a very experimental #2 in FlyLo while Kid A was the runner up to Jane Doe, also mirrors the 2000-2009 feature in a striking fashion. I guess the more things change, the more they stay the same. :-)

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

more importantly how the fuck did it even place in the top 10

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

when I was looking at some other folks lists, i suspected that some of us were maybe a little pre-disposed to multiple artists (even if it was a question of placement over inclusion). Not everyone and not every list, but I remember suspecting it was the case for some of us (and ultimately I determined that it was the case for me...).

What resulted was that artists with multiple god-tier works probably split votes, or split placement strength. We have a consensus amplifier when we do the final count, but this applies to individual albums, not artists. So when you see multiple entries from singular artists, you should keep in mind that there may have been factors working against that from happening, which makes it more impressive, given the obscenely diverse set of lists...

also keep in mind that the folks Sowing listed are just those who contributed to this feature... there were a ton more lists from absentee staffers or emeriti that figured into the end ranking...

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

Still a little perplexed by the lack of metal that made it to the top 100, relatively speaking, but that's not a complaint.

04.10.20

04.10.20

Also, fantastic job on the write-ups. Especially that FlyLo one. Goddamn

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

That's on me. I missed it while doing my editing. Thanks for bringing it to attention.

I'm more surprised that Pale Horses got #7 than I am that Home... got #1.

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

A Silver Fox still gets me 8 years later

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

Then again who knows. I was 15 when the last decade list came out and going through that list was a formative experience for my musical taste. Back then the staff writers were infallible beings that knew loads of obscure shit. Now I’ve interacted with these staffers, called them plebs in the emery/babymetal/whatever other meme thread, and generally don’t take anything on this site as seriously.

Regardless, this list elicits a profound sense of disappointed nostalgia.

04.10.20

04.10.20

It's more innovative and influential than literally anything else on the entire rest of the list so yeah no its spot is more than earned. If anything it should be a spot higher.

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

Lol, Sput equivalent of a huge boomer take. As though any other side would have put Jane Doe at #1/as though that album hasn't enjoyed umpteen years of self-cultivated mythos here

04.11.20

Sweet

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

Big agree

04.11.20

04.11.20

i'm telling you to calm down because me expressing disagreement only constitutes as defensiveness to you because you're hyper-sensitive

04.11.20

04.11.20

wait, wot?

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

I disagree I think being willing to put the same artist twice makes for a more honest list. Like why should The Money Store or something make the list over Sleep Well Beast just because there's already a National album much higher, despite the staff obviously enjoying the latter more than the former?

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

menzingers bitch

04.11.20

Not on our list.

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

Ha ha. There's more than cropping. There's cutting, background removal, and pasting too, to get the band logo/album title into the cropped artwork. Still not hard, but still...

04.11.20

Acts IV or V deserve a mention tho :( . V is easily one of my top 10 records of the decade.

04.11.20

04.11.20

Ok

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

I know right, why are The National on this list

04.11.20

04.11.20

I find most of his stuff incredibly boring, so I kinda agree with you on this one.

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

not gonna lie, this made me laugh

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

/clownface

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.11.20

04.12.20

04.12.20

04.12.20

04.12.20

04.12.20

04.12.20

04.12.20

04.12.20

04.12.20

04.12.20

come on man i worked hard on that write-up

04.12.20

04.12.20

04.13.20

04.13.20

04.13.20

04.13.20

04.13.20

04.13.20

04.13.20

04.13.20

04.13.20

04.13.20

04.13.20

04.13.20

underrated comment

04.16.20

04.16.20

04.16.20

04.16.20

Not that I think "this isn't good enough" or something... but I was comparing staff lists to the global lists throughout the years and they tend to turn out pretty differently, yet still feel very sputnik. Would be cool to see the other side of the coin... though I'd imagine it's a different beast with users having a whole decade of albums to vote for instead of just one year, might end up looking like the charts with that big a sample size.

04.18.20

04.21.20

But nice to see FlyLo, Jenny Hval and both Aviary/HYIMW by Holter!

04.21.20

04.21.20

04.21.20

04.21.20

04.21.20

04.21.20

04.22.20

04.22.20

04.22.20

04.22.20

04.22.20

04.23.20

04.23.20

04.23.20

Hahahaha what a terrible top, seriously.

04.23.20

04.23.20

04.23.20

04.24.20

04.24.20

04.26.20

04.27.20

05.01.20

Pale Horses in the top 10. My favorite mwy album and one of my favorite of all time. Rainbow Signs is a f-ing masterpiece

05.05.20

05.09.20

05.09.20

I hope users did better with their list

05.09.20

05.12.20

05.14.20

12.03.21

12.03.21