100-76 | 75-51 | 50-31 | 30-11 | 10-1

50. Fair to Midland – Arrows and Anchors

One of the graver losses of the 2010s, Fair to Midland outdid themselves with sophomore (and ultimately final) album Arrows and Anchors. While the band have straddled genres from alternative, metal, folk, and prog throughout debut Fables from a Mayfly, Arrows and Anchors managed to tighten up the band’s genre fusion, drive the sound into heavier territory, dial up the catchiness of nearly every track on the LP, and reinvent timeless children’s story Rikki Tikki Tavi into something you can headbang your brains out to. Need I say more?

Darroh Sudderth’s vocals remain as iconic as ever, warbling with passion as he projects clever twists of common sayings over fuzzed out guitars sparkled up by just enough keyboard to transform a dirt foundation into a more respectable pavement. Describing Arrows and Anchors can sound almost formulaic, but each and every track is just so much fun that it’s hard to care. While every track manipulates the ratio of keyboard twinkle to guitar crunch to similar spectacular results, the meat of each is seasoned just appropriately enough to feel freash and fun. There’s an undeniable menagerie of influence and expertise compiled into Arrows and Anchors, but ultimately it’s the the levity of the music and lyrics like “If opportunity knocks, let’s make him beg” and “If he tries to shake your hand, just hit him with a frying pan” that elevate Arrows and Anchors beyond a standard prog rock obelisk of awe into a lasting and well-traveled temple of fun. –AtomicWaste

49. Joanna Newsom – Have One On Me

Infamously stretching through three discs and at two goddamn hours long, Have One on Me remains amazingly stripped-down and palpable. An artist like Joanna Newsom was always going to be punished by a vocal minority for her musical ambitions–after all, she chose the putatively antiquated harp as her instrumental vehicle–and her third album’s extraordinary length will immediately turn off those allergic to (putative) pretense. Fuck ’em, I say: Have One on Me is less like John Gower’s agonizing Confessio Amantis, to take a medieval literary example which might seem appropriate both to Newsom’s fans and her detractors, and more like, I dunno, Tame Impala’s Lonerism or, dare I say it, The Beatles? Mama’s Gun, maybe? I am, here, practicing free association at its freest and most associative, but I think there’s something to be said about each album serving as a document of the creative process run wild and yet reined in and controlled in an uncanny way. An album like Have One on Me demonstrates something like the opposite of writer’s block, and like those other albums, it evinces a sense of warmth toward people and the world they occupy as a weird but eminently satisfying byproduct of its artistic surplus. There are great ideas–and, therefore, love?–seeping out of every pore.

This is on par for Newsom, who is as talented and generous an artist as the 21st century has produced, her label’s opposition to bringing their music to the streaming masses notwithstanding. But there’s something deeply special about seeing her meet a new audience halfway on Have One on Me while wholly refusing to tamp down her sense of idiosyncrasy and, yes, excess. And while a couple of songs could indeed stand to be cut down to 6 minutes instead of 8 or 5 instead of 9, the whole package is so warm and enveloping that most moderately patient listeners won’t mind.

The vast scale of, and panoply of melodic ideas on, Have On on Me makes it unusually difficult to talk about structure, as I often like to do. But the formal coup that occurs at the very ending of the album renders the whole thing, all two hours, profound and heart-rending. First, as the set-up, there’s the ravishingly defiant build that occurs about five minutes and twenty seconds into “In California”: “I don’t belong to anyone / My heart is heavy as an oil drum,” Newsom sings over swelling strings, and we’re left to pick apart her stance on her own solitude. And then, probably some 90 minutes later, comes the breakup song and album closer “Does Not Suffice,” with the very same melody materializing like an apparition, only this time it’s a string of “la-la”s that trail out of her mouth. Finally abandoning her oft-remarked-upon vocabulary, this consummate artist succeeds in voicing unspeakable pain and ecstasy. Whatever travails life throws at her Newsom has an answer for. Would that it were so easy–but art, in the end, is all about perfect illusions, isn’t it? –robertsona

48. Converge – All We Love We Leave Behind

All We Love We Leave Behind wields a crystal clarity not really present in the band’s other works, from the cold punch of its production to the painfully lucid proclamations on love, loss and abuse. There’s a sense of something that could almost be called resignation, but I think it’s more so the transformation of youthful fury into sobriety, a more candid recollection of traumatic events. Compared to its successor, 2017’s The Dusk in Us, All We Love We Leave Behind hits with a more direct sting, as if it were caught up right in the midst of personal revelations; for instance, opener “Aimless Arrow”, with Ben Koller’s drumming throwing a flurry of punches from the very start, mourns the unerring trajectory of someone who has fallen to a pattern of dysfunctional relationships. The title track, as well as “Glacial Pace” and “Coral Blue”, exemplify that newfound awareness and composure; the latter two can be seen as the designated slow-burners, a submersion into increasingly icy waters, while “All We Love We Leave Behind”, propelled by an urgent guitar line, is a poignant apology from Jacob Bannon for the emotional toll of touring on his loved ones. –clavier

Clichés aside, Quarantine changed my life. It truly did – for a solid year, everywhere I went, Quarantine accompanied me. It was the soundtrack to many of the changes I went through, whether it were voluntarily, by force or by circumstance. Yet, after all this time, the feelings I had when I first heard “Light + Space” are still fresh in my mind, still raw and all the more existentially melancholic. Quarantine is an album that illustrates its creator’s own alienation from others and of her own surroundings, viscerally tearing down any notion that something could change for the better, employing this morbid sense of deathly cynicism to implant an underlying feeling of despair – thinking of “Tumor” in this moment with a barbed lyric like “The signal keeps cutting out but one thing is clear / Nothing grows in my heart, there is no one here.” It’s so blunt yet the music masks it with dense forests of lethargic synths, dense sampling and cold atmospherics. Even moreso now then back when it was new, Quarantine is the soundtrack of the times, of what we’re experiencing now, whether it’s from the view of something with unwavering optimism or with cautious skepticism. –Frippertronics

46. St. Vincent – Strange Mercy

It’s hard to fault St. Vincent for dissolving her own sound in acid when the decade changed. Early reviews of Annie Clark’s indelible, incomparable pop focused more on her physical features than anything regarding her actual talent; even the consistently wonderful Actor had its warped-Disney deconstruction of the suburban housewife stereotype largely lost on the critics. So with Strange Mercy came both a new kind of brashness, and a surprising subtlety and space in the songwriting. It’s hard to imagine a lesser album making room for the delicately bruising “Champagne Year” alongside a hyper-powered barn burner like “Surgeon”, let alone the arch pop leanings of the title track and “Cruel”. It’s all held together, shocker, by sheer talent. Clark’s voice is one of the most incredible in the game, pirouetting up and down her not-insignificant range like it’s running away from a deal gone bad, and when she amps up the guitar into righteous absolution you fucking feel it in your bone marrow.

As time has gone on we’ve started to find how intertwined Clark’s complex family life is with her elusively emotional music. This kind of thing enhances Strange Mercy, but never defines it. Do you need to know Annie Clark’s father was jailed in 2010 to feel the fire rising off a line like “if I ever meet the dirty policeman who roughed you up…” singeing your fingers? No, but the glimpses into a real life behind the layers and layers of irony, commentary and talent are fascinating to have, and never as emotionally resonant as on St. Vincent’s 2011 masterpiece. –Rowan

Diamond Eyes could, and should, be accounted as the most important album of Deftones’ career, and for a myriad of reasons. The scenario the band found themselves in with this record is one that would test every fibre of a person’s being. During the Eros sessions, it’s no secret that the band was at its breaking point and looking at an imminent oblivion – with relationships and communication on the brink of collapse. Then Chi Cheng’s accident happened, sending shock waves into the camp and putting a completely different perspective on everything. This forced Deftones to reassess their lives and push forward for their brother Chi, shelving [the now elusive] Eros and starting from scratch with their old friend Sergio Vega as a fill-in on the bass. The end result was a blinding return to form that imbued a different kind of energy for Deftones; a revitalisation and purpose unprecedented by previous albums’ standards. That awful situation brought out an intensity to Diamond Eyes‘ music – a circumstance that challenged and questioned everything they were doing at the time of its making.

The quality speaks for itself though; Chino’s beautifully soaring melodies – which are lathered in mourning – pay tribute to Cheng perfectly on the likes of “Diamond Eyes”, a performance that masterfully balances grief and optimism with irradiated brilliance. The instrumentals are some of the heaviest the band have ever produced: Carpenter’s foundation-destroying riffs on “You’ve Seen the Butcher” and “Rocket Skates” deliver the potency of their endeavours, while “Sextape”‘s lethargic tempo drives the ethereal poignancy the band is so well known for. It’s an airtight forty-two minute album that displays a band backed up into a corner and unwilling to let life’s curve balls get the better of them. Few bands recover from this kind of tragedy, but Deftones take the situation, make a stronger foundation, and serve up their finest album to date. –Simon

44. Mount Eerie – A Crow Looked at Me

At this point in my experience with, or of, A Crow Looked at Me, I find it hard not to sing along. There’s something a little perverse about that (the album being, amongst other things, a diaristic account of a husband’s loss of his wife). But what we shouldn’t forget is that Crow is, after all, a piece of music. A drab piece of music, sure – music attached to a particularly heady, heartrending context – but music nonetheless. When the audience laughs, then, at the first of ‘Now Only”s strikingly bouncy choruses: People get cancer and die / People get hit by trucks and die / People just living their lives get erased for no reason / With the rest of us watching from the side…and Phil asks, “Why are you laughing?”, and the audience goes silent, I can’t help but think the answer obvious: “because that’s the effect of Mount Eerie’s art”. Of course that’s too obvious; I might be missing the point. But what Elverum does on A Crow Looked at Me is in no unobvious terms explore the limits – cast into doubt the efficacy and morality – of his art, maybe all art. All whilst continuing to do art.

Which isn’t to argue that A Crow Looked at Me is in any sense immoral; but it is, perhaps, selfish… or, at least, self-indulgent. An abstraction of an abstraction of the abstraction that is death. For an audience, or the world. For, most definitely, Elverum himself. My singing along to A Crow Looked at Me is, likewise, for me. I’ll forever smile and laugh and weep at its words and melodies – attach meaning where there is none, and filter it through context read and known and experiened, as well as that not read or known or experienced. I’ll sing along because Crow is, despite what anyone argues, music. Drab music – much more than music – but music nonetheless. –BlushfulHippocrene

43. Bon Iver – Bon Iver, Bon Iver

The intimate debut record by Bon Iver, For Emma, Forever Ago is widely lauded as Justin Vernon’s masterpiece. However, it’s clear that the self-titled album by his band is the peak of their abilities for numerous reasons. This follow-up comes more from a group effort, and it shows. This album deals with some of the same themes like love lost and finding one’s place in the world, but sounds remarkably different, being incredibly open and universal thanks to an adventurous musical palette including expanded instrumentation and willingness to traverse numerous genres. The compositions are unpredictable and always beautiful to behold. Elements of indie rock, electronic music, and more instruments are added to the band’s sound to make for heartfelt songs like “Minnesota, WI,” “Holocene,” “Michicant,” and “Calgary.” Vernon expresses his wanderlust and asks big questions in a truly profound manner throughout, opening himself to the world after the introspective nature of For Emma, Forever Ago. Bon Iver would go on to pursue a more art pop and electronic direction in the future, but Bon Iver, Bon Iver marks a special time for the group, one that sounds truly fearless and open-hearted. –Ben K.

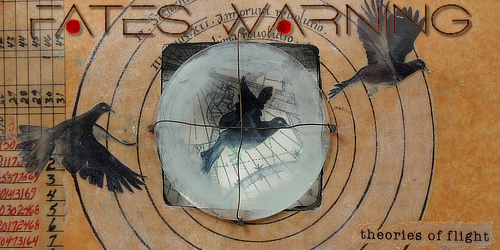

42. Fates Warning – Theories of Flight

Fates Warning didn’t invent progressive metal and it wouldn’t be a shame to admit that they never reached the highs of Dream Theater or even Queensryche. But they have certainly aged more gracefully than the aforementioned bands; so much, where one can make a case about them having released their best effort so late in their career. Fusing the catchy songwriting of Parallels with the heavy riffing of Jim Matheos and the signature style of drummer Bobby Jarzombek, Theories of Flight features the best of both worlds. Melancholic, accessible, atmospheric, modern, and non-indulgent, Fates Warning’s 12th LP sums up perfectly what this titan is all about. Everything on here flows naturally, to the point where the album’s highlight, and one of the crown jewels of the band’s discography, is the 10-minute “The Light and Shade” of things, which would also be a strong candidate for metal song of the decade.

However, it’s not just the musical aspect that it’s important here. As part of the Big Three of progressive metal and as one of the more well-known names, a strong effort by the American progsters can potentially bring new fans to the genre. Maybe more importantly, Fates Warning’s latest endeavor is not only one of the best progressive metal albums of the decade, but the apotheosis of songwriting and emotion in a genre that sometimes tends to forget those virtues. –manosg

41. The Dear Hunter – The Color Spectrum (Complete Collection)

It’s no secret that Casey Crescenzo and The Dear Hunter have been making incredible tunes for ages, but to embark on a project of 9 discs each of a different color with a unique interpretation of the theme and style for each color… Well, that seemed ambitious even for the guy successfully writing a six act concept album series about a World War I vet and his tangled love affair with a prostitute, a priest, and a war. But while acts I through III had already solidified the band’s prowess as prog rock innovators, The Color Spectrum proved to the world there was nothing The Dear Hunter couldn’t do.

While the Violet record conforms most closely to the sound heard on earlier releases by the band, Black takes on an industrial metal feel, Red, grunge-tinged heavy rock, Orange, a taste of funk and the 70s, Yellow, a bright and sunny beachy theme, Green, blues rock, Blue, a downtempo setting blending folk, rock, and blues slides, Indigo, firing The Dear Hunter into a beautifully unexplored electronic chill space, and White focusing on bright pianos, acoustic guitars, and powerful minimalism. While the variety itself is impressive, there’s flat out astonishment in the fact that the group’s execution is nearly flawless in creating four hits in each style on each disc – without a misstep to the theme established by the color.

There’s something for every mood, and that something is exceptional in every case. That said, Indigo stands out as an exceptionally strong disc – perhaps for its striking difference to the rest as the only electronic disc – as does White, for the enhanced impact of its exploration of spiritual lyrics among simple but effective arrangements. Blue and Green, on the other hand, are discs I come back to less frequently – but I recognize that has more to do with my own headspace than the content offered by those portions of The Color Spectrum, as they’re far more melancholy than the rest.

Ultimately, it would be easy to write off The Color Spectrum as a gaudy exercise in self-aggrandizement were it anything less than perfection. But the material is so strong that the passion invested in the project demands it be considered otherwise – among the bests of the decade. And if that same material demands that The Dear Hunter be recognized as exceptionally talented and versatile in the process, well, so be it – it’s just the truth of the matter! –AtomicWaste

To this day, I’m not sure how to pin down Sad Light and its quirks — call it dreamy slowcore, call it sleepy absurdity-tinged indie rock, and you wouldn’t even be wrong. It straddles a strange boundary between childlike humour (perhaps also naïveté), crushing disillusionment and medicinal haze; there’s a sort of half-lost (or is it half-retained?) innocence that breaks our hearts each time it runs headfirst into an obstacle, and elicits bittersweet sighs as it encounters brief moments of respite, settling into a state of blissful, willful ignorance. Interestingly, a recurring lyrical device is the intentional use of agrammatical sentences to convey a sense of childishness — a solid dose of humour to an album that can be surprisingly crestfallen at times.

The choice of “Horse Pill”, charmingly jaunty and jangly, to open up Sad Light immediately reveals the album’s underlying bite; “Horse Pill” critiques the pharmaceutical industry and its push for wellness in a bottle, with a flippant description of the robotic functioning under medication — “why don’t you pick it up from your doctor’s office? Plug it on in, see if you can function, wipe it on your shirt, make sure the battery works.” “Jeju Island”, meanwhile, lays bare its environmentalist message with a startling frankness that belies its dreamy, star-filled atmosphere: “and when all of his currency chews through the forestry and into the blue, will regret pound his head like a crown, watching habitats ripped from the ground?”

A subtler, but nonetheless fascinating contrast is that between Sad Light‘s childish playfulness and its more adult sensuality. “Somersault” and “Witching Hour” are not unlike the fever dream versions of childhood memories, filled with oddly specific asides and nonsense scenarios — the former mentions breaking into an amusement park and “a ferris wheel that never ends”, whilst the latter contains the following: “so then I crab walk to the park, I’m painting pictures in the dark but there’s couples hand in hand”. On the other hand, the “15 Step”-inspired title track depicts, with much more seriousness, a sensuous vulnerability: “your skinny body is so brittle*/ I let my guard down easy now*/ I crawl up and ask you*/ once, hover to the bedside,*strip your ribs and come to me?*Bend as we sleep?”

I remember that Dylan Glover, ITEM’s singer, said that Sad Light was an ultimately optimistic album; I think it’s at least in part because, despite its moments of melancholy and disillusionment, it manages to maintain a pure heart from beginning to end. In other words, it’s an incredibly earnest, perceptive work that bears no self-consciousness, no resentment or bitterness; it’s the sweetest solace to be able to bathe in its sparkling synths and fantastical scenarios, with the knowledge that levity never strays farther than from the corner of your eye. –clavier

Pardon the bachelor’s degree English lit reference, but the way Wheel encompasses all of life reminds me of James Joyce’s Ulysses. Laura Stevenson does what Joyce did best (albeit with a much shorter runtime): she tackles all of life’s complexities along with all its mundanities. Wheel ends where it begins, it builds itself up in sequence, repeats things in a way you’ve never heard, like life, it turns itself over like a wheel. Wheel is a woman laid bare, it’s the epitome of unpretentiousness. It’s about the real kind of getting better, the kind where you get to the end and then start all over again. –Trebor.

As far as indie rock wunderkinds go, Alex Giannascoli is a bit of a mystery. His albums tend toward the misshapen; folky masterpieces are assailed by stacked experiments in the tracklist, or by their own protracted melodies. The goat/ram hybrid on the cover of (Sandy) Alex G’s 2017 breakout Rocket portends the kind of audience engagement offered by this gnomic artist. Portraits of animals possess a unique kind of energy, because most of us don’t think of them as having an inner soul to project through their eyes and posture. The animal standing in the grass looking directly at us, as painted by Giannascoli’s sister Rachel, locks us into his fundamentally unknowable stare. So it goes with Alex G, who engages us profoundly without revealing too much of himself.

Like Frank Ocean’s Blonde or Laurel Halo’s Quarantine, then, Rocket employs a number of distancing effects in its structure and sound to this particular end of obscuring or at least complicating the delivery of emotions and proclamations to listeners. Fans of alternative R&B and its telltale lush keyboards will find their ears perking up at the first verse of “County,” but then, watch out, here comes the bluesy, dissonant breakdown, contorting the song’s form until the relieving return of the R&B motif…but everything is all weird now because of the breakdown—not to mention those lyrics! How about the tick-tack percussion of “Horse” and its presumptive partner-in-crime “Rocket”; the way ominous opener “Poison Root” suddenly just becomes the swinging “Proud”; the Auto-Tune shoehorned into “Sportstar”; even the terse song titles, and that album cover? Every conceivable element of this album is worked out to point up the fundamental sense of persistent enigma within us all.

And then there’s its centerpiece, the immeasurably moving alt-country ballad “Bobby”. Harmonizing oh-so-perfectly with one Emily Yacina (MVP, for real), Giannascoli spills out everything. The titular Bobby is “just a friend of mine,” by Alex G’s account, but the seemingly casual nature of their relationship is undermined by the pain in his voice when the first chorus comes around: “I’d leave him for you, if you want me to.” Even all this scans as a mystery: who is Bobby? Who is this unnamed interlocutor, this “you,” who might ask them to separate, and why is Giannascoli willing to leave his beloved Bobby for that person? What does it “mean” about the song’s narrator-protagonist that Yacina and Giannascoli sing the whole song together? Jesus fucking Christ is “Bobby” good. Much, much more than the sum of its oddball parts, Rocket is, as a result, one of the most endlessly repayable indie albums of its time. –robertsona

37. Lana Del Rey – Norman Fucking Rockwell!

Lana Del Rey’s immense level of talent has always been self-evident. Her vocals soar with a sense of eloquence and dire purpose; a voice that sounds like it was meant to speak to an entire generation. The problem is that across five full-length LPs, that destiny was never fulfilled. She wrote some absolute hits – namely ‘Born to Die’ and ‘Video Games’ – but she could never quite string together a complete album of songs worth listening to. Well, Norman Fucking Rockwell! is the album that we’d been screaming for since she first flashed potential at the beginning of this past decade – a front-to-end masterclass in songwriting that, in partial debt to Jack Antenoff’s brilliant production, showcases her voice to its maximum potential. All of this liberates Del Rey to do what she does best: wax poetic about America – or in this case, its demise.

Norman Fucking Rockwell! revels in its apathetic apocalypse; Del Rey sits back coolly and sings about it all like a passive spectator – someone who can easily see the fire on the morning’s horizon, yet knows that it’s too late to turn the Earth backwards to yesterday. With this mindset, we’re given drunken nights spent partying, fucking, and getting high – it’s a “too late” mentality that is rather certain of what our fate will entail after the next page-turn within the book of life (“If this is it, I had a ball” / “I guess I’m signing off after all”) and very much in a state of post-panic. Within Norman Fucking Rockwell!‘s almost shell-shocked calm, we’re given a handful of Del Rey’s most breathtaking ballads: ‘Venice Bitch’ in its nine minutes of clear-eyed lucidity, dreamy soft-rock elements, and psychedelia; the breathy whispers of ‘Mariners Apartment Complex’ underpinned by gorgeous classical pianos; the momentous anthem for women’s rights that is ‘hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have – but i have it’; the subtle jabs at the presidency in the title track; the humor and sadness that ‘Happiness is a butterfly’ emits with that ridiculously infectious chorus…it’s all here. Norman Fucking Rockwell! beckons for us to join in on the anarchal apathy, light one up, and gaze into the eyes of a loved one. Because after the record stops spinning, we don’t know if we’ll get another chance. –Sowing

It took getting caught in the rain to realise I loved James Blake. Accuse me of spewing cliché but something in Blake’s notes, or the space between his notes, conjures such an image of drizzly, lonely London, of ghost notes echoing down hallways of fog where someone walked ahead of you just a minute ago. What I’m saying is when I hear the grey strains of “The Wilhelm Scream”, one of the most finely constructed songs of the decade, it puts me right back in that space: ducking inside a bookstore to avoid the downpour, waiting it out for half an hour with James Blake in my headphones, for the first time letting it work its magic on me.

Blake’s true talent, I think, is beyond his (incredible) treatments of vocals or production, and more the completeness of the images he can conjure with a few sparse words. How “Lindisfarne”‘s bare lyric places us on a small island off England in a meditative state, but that shaking, unsettled guitar suggests something more twisted. How “I Never Learnt to Share” gave us one of the most quotable, stupidly devastating couplets of the decade and repeated it ’til that shit was drilled into our skulls. But he may be at his best recontextualising the words other people have written, whether by his father on “The Wilhelm Scream” or Feist’s “Limit to Your Love”, pairing desolate tales of loneliness against slowly escalating tidal waves of rumbling bass and glitchy textures. Even when Blake just lays down a vocal over clean piano, as on the genuinely sweet “Give Me My Month” and heartbreaking “Why Don’t You Call Me”, there’s a fractured nature to the writing and song lengths deliberately cut short, as if Blake wants to emphasise the ambiguity and strangeness of life. Maybe water pours from the sky in the middle of a dry autumn like divine judgement; maybe a hallway of fog resolves into the face of a friend you haven’t seen in too long, the one you were just thinking you should call and mend a broken bridge. For either extreme, an album like James Blake is there, never failing to capture the moments between moments too fleeting to identify. –Rowan

35. Sharon Van Etten – Are We There

Sharon Van Etten writes like the clattered, streaming subconscious of all of us: uncertain and afraid, sure (don’t let that opener fool you), but also loud, fast, and mean. Hers is a personal narrative that becomes uncomfortably universal among the cavernous and steepled indie rock soundscapes that she has now fully absorbed from producer Aaron Dessner and his group and made her own. 2012’s Tramp was a singular case study in a singer-songwriter’s unrivaled control of tone and texture, the announcement of a talent arrived, fully formed and emotionally bare. Where Tramp outlined what Van Etten could do, Are We There is that potential realized, a bloodletting that refuses to give its subject any hint of a respite. It’s a draining, exhausting listen, but a fulfilling one, as well; facing one’s demons like Van Etten does here—again, loud, fast, and mean—is as cathartic a therapy as there is. Are We There remains an incredibly nuanced listen, with that National house style best likened to a majestic low roar, one that shapes itself around Van Etten’s sinewy vocals and light shadings of keys, spartan beats, and aching guitar. Yet the focus remains, as it should, on Van Etten’s own vocal prowess and lyrical switchblade, one that runs the gamut from the barely controlled rage of “Tarifa” to the numbing grief on “I Love You But I’m Lost”; and that’s just one stunning back-to-back sequence among many, many others. That she sounds just at home on the spindly, musically sparse “I Know”, picking splinters out of her heart, as she does on the grand, rollicking thunderstorm of “Your Love Is Killing Me”, is a testament to the breadth of her vision and the depth of her songwriting.

Better yet, the playfulness that characterizes Van Etten’s live show and interviews permeates Are We There to a greater extent than any of Van Etten’s work. Combined with her innate pop instincts, tracks like “Taking Chances,” the gossamer ballad “Our Love,” and closer “Every Time The Sun Comes Up” reveal a healing process that is as joyful as it is effective. It’s certainly the only album I’ve heard this decade where taking a shit was effectively the record’s capstone. That Are We There with Van Etten goofing off in the studio tells you all you need to know about the act of so bravely opening herself up to the world means to Van Etten. Laughter remains the best medicine. –klap

There’s something deeply satisfying about seeing an artist finally reap all the successes they so richly deserve. For the better part of a decade prior to the release of My Woman, Angel Olsen had been putting out a series of increasingly great and raw folk records, culminating in 2014’s spectacular Burn Your Fire for No Witness (26th on Pitchfork’s decade list! Sadly absent here). My Woman, though, was Olsen’s Almost Famous moment; suddenly, there was actor Christina Hendricks, dancing in the front row at a Los Angeles show while Miley Cyrus took selfies backstage with the vinyl LP in her mouth. Suddenly, there was Olsen, playing the big-time stages at festivals like Coachella and Glastonbury. You can hear why: an intoxicating mixture of classic Laurel Canyon singer-songwriter, ’70s glam, ’60s girl group, and, most importantly, a bloody pop heart, Olsen’s fourth record is unflinching in its dissection of relationships both sexual and something else, obsessed with love and lust and volatility. It paints a painfully detailed portrait of Olsen travelling from awkward and shy (“Never Be Mine”), to dangerously obsessed (“Shut Up Kiss Me”), to the wistful “Those Were The Days”, a narrative arc that follows a traditional Side A and Side B pattern. The spartan, smoky “Pops” lays the devastation bare at the record’s conclusion: “You can go on home, you got what you need / take my heart and put it up on your sleeve / live out your life, I’ll never tell you you’re wrong / baby, don’t forget, don’t forget it’s our song / I’ll be the thing that lives in the dream when it’s gone.”

In “Pops” and elsewhere, Olsen may seem crippled by these experiences — “All my life I thought I’d change,” she sings and sings again on “Sister”, as if the act of repetition will make it true — but the path of My Woman is one of growth. The playfulness of “Shut Up Kiss Me” belies deep-seated insecurities, until “Heart Shaped Face” finds the strength to realize those insecurities are just excuses for another’s fuck-ups. “Woman”, meanwhile, inverts the ostensible torch song by making it a passionate middle finger: “I’d do anything to see it all, to see it all the way that you do / but I’d be lying baby, lying to you.” That “Woman” ends with a Stevie Nicks-ian vocal, powerful and soaring (“I dare you to understand / what makes me a woman”), and a guitar part that screams its defiance is the strongest evidence yet that this is not something ruinous but instead a triumphant severance, Olsen decisively reclaiming her agency. That unbreakable sense of self carried over into 2019’s titanic Lark, a record that adamantly proved Olsen wasn’t ready to cash in anytime soon. As the decade that made her a headliner ended, Olsen was still aiming for bigger, better things, still doing what she does best: going for broke. –klap

Tucked away snug in my warmest, most indelible memories is the first time I remember visiting my Grandparents in Christchurch. My Grandma took me on a walk to the park, pointing out birds and delighting that I got to see my first fantail. We went to get ice-cream in the park while a Te Puoro Maori group were playing, swinging by KFC on the way home – the first time I’d indulged in that particular delicacy. I saw my first tuatara on that trip and befriended a cousin over games of “Old Maid” with a bond that endures. Forward a decade and a half, my Grandma passed and dearly missed, and I’m listening to the wonder in Mark Kozelek’s voice as he says “it was the first time I saw a hummingbird” and I completely understand.

I hear it everywhere. Mark Kozelek intones “speak memory” into a mirror and throughout the deaths in the family, personal recollection and news items used to focalise Kozelek’s own mortality (“The Sopranos guy died at 51 / that’s the same age as the guy who’s coming to play drums” Kozelek frets over an acoustic guitar line so forceful and ugly it sounds percussive) we learn that life is precarious, fragile, ephemeral, fleeting. Carissa is especially moving in this regard, not just sorrowful but a Tragedy because we know Carissa, can appreciate the difficulties of being a teenage Mum turned Resident Nurse without having them stressed, and we know her fate was a cruel accident.

Yet, in his neatest trick, Benji is life-affirming. Even in her death, his family were ‘there the whole way through’ for his beloved Grandma now gone; in a beautifully succinct encapsulation of the album, upon learning of a friend’s death he boards his train feeling “somewhere between happy and sad”, a line I’ve always interpreted as about life itself. People may come and go, and they do, and tragedy may strike – but the warmth, the happiness, is always there if we let it in. I hear the lilting interweaving guitars that close “I watched the film The Song Remains the Same”, the slight atonality one of my favourite moments in music, if I need to be calm, “the sports bar shit” when I’m in a shit sports bar. Yes, the album has permeated; but I am as happy to be in its thrall as I am to be to those loved ones gone, loved ones here, loved ones I’ve yet to meet; confirmation of a life not just lived but affirmed, celebrated, joyously incomplete — somewhere between happy and sad. –Winesburgohio

32. Janelle Monae – The ArchAndroid

2007’s Metropolis: Suite I (The Chase) was an intriguing and unusually high-concept piece of arty neo-soul, but The ArchAndroid announced the arrival of a generational talent. Drawing from more diverse conceptual and sonic influences than you can shake a stick at, Janelle Monae opened up her 2010s with a record that gleefully breaks boundaries, one that ceaselessly prods and yet also reshuffles the pleasure receptors in its listeners’ brains. The ArchAndroid is the rare concept album where the concept keeps on kickin’ through the runtime and yet never swallows up the music in its zeal; the result is a delectable concoction of psychedelic soul and funk in which Monae’s political preoccupations and her storytelling prowess dovetail perfectly with so-good-you-want-to-laugh chord progressions. From “Locked Inside”‘s splashless Stevie Wonder worship (seriously: listen to that shit and Innervisions‘ “Golden Lady” back to back) to the inimitable build of “Tightrope,” which for some reason amazingly incorporates “Happy Birthday,” to the immensely moving droid-soul of “Mushrooms & Roses”–each piece, sans perhaps the much-maligned Of Montreal collab “Make the Bus,” fits into the whole and is deeply pleasurable in itself. The thrill of listening to The ArchAndroid front to end is, to my ears, unmatched by any other work this decade. Monae’s intelligence and generosity sparkle. More than vast in the ground it covers, more than great in its verve and intent, The ArchAndroid is perhaps, appropriately enough, more than human. –robertsona

31. Brand New – Science Fiction

Science Fiction‘s release was almost as memorable as the album itself. Brand New essentially trolled the hell out of their rabid fanbase by – after an eight year wait – nonchalantly announcing pre-orders for a very limited vinyl “LP5” via a Facebook post (they sold out within minutes – trust me, I tried to get one), and proceeded to overnight some fairly raw-looking, unlabeled CDs containing the entire sixty-one minute LP on a single track to everyone who pre-ordered. Then, just as inner circles began to stream and leak the album, Brand New made the entire thing available for purchase via their website. Anyone who was a part of that experience can attest that it was a pretty wild ride.

Once released, Science Fiction only saw Brand New’s legend grow. The album feels like an anthology: Deja Entendu-styled hooks burst forth from ‘Can’t Get It Out’, ‘Waste’, and ‘In the Water’; the dark lyrical content and riff-bolstered approach of The Devil and God are Raging Inside Me is evident within the earth-shattering solo of ‘137’ and the coarse screams that drag across ‘Same Logic/Teeth’; all while the eerieness and wiry experimentalism of Daisy makes itself plainly known within all those intros, outros, hidden tracks, audio samples, and backwards passages. It’s the ultimate Brand New experience for anyone who’s been a fan since their inception.

Despite the fact that Science Fiction resembles more of a resume-to-date than an evolution, it still feels like its own entity. The band has never come close to writing anything as haunting as ‘Lit Me Up’, or as forlornly nostalgic as “Batter Up’. They celebrate their career as well as the support of their cult-like fanbase at nearly every turn, scattering allusions to the band’s demise across the record’s hour-long runtime. Science Fiction makes an art form out of treading familiar ground, all without Brand New ever truly retracing its steps. It’s an incredible swan song, and one that rightfully ties the knot on what could be considered a perfect discography. –Sowing

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

his latest is a bit less constant but the highs are his highest.

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

DECIIIIIIIIIIIIIIDE

YOU'LL THROW ME A LAME WAIT SHIT OUT

IT'S A LITTLE LATE

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.08.20

04.09.20

04.09.20

04.09.20

04.09.20

04.09.20

I'm not, and I was actually a tad surprised it made the list - let alone as high as #31. I'm glad, though. It deserves to be on here and I think it's in exactly the right sort of placing when you consider the composite average nature of these lists.

04.09.20

04.09.20

04.09.20

04.09.20

04.09.20

04.09.20

04.09.20

04.09.20

04.09.20

04.10.20

04.10.20

05.02.20

05.02.20

05.03.20

07.07.20

07.07.20

07.07.20

07.08.20

07.08.20